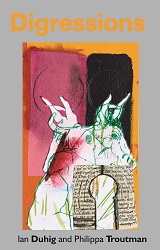

Digressions

Ian Duhig

Price: £7.95

In 2013 – the tercentenary of the birth of Laurence Sterne – Philippa Troutman and Ian Duhig started digressing, getting lost in time and space around Shandy Hall. They chanced on riches from Viking ghost stories to Conceptual Poetry, in a meteorite-riddled topography of forgotten monuments, mazes, ruins and traps, sharing their discoveries and creations in texts, exhibitions and online. The results range from the humorous and moving to the fascinating and macabre, engaging and extending Sterne's legacy for the twenty-first century.

‘He lives in Leeds, completely out of the literary world.’ John Freeman, ex-editor Granta ‘Thrillers like The Da Vinci Code are key indicators of contemporary ideological shifts’. Slavoj Žižek, In Defence of Lost Causes For what might break a writer’s block that grips my pen as if King Arthur’s sword, I quest through bookshops of My Lady Charity in Urbs Leodiensis Mystica, completely outside Freeman’s (as most) worlds, where locals speak blank verse (says Harrison); Back-to-Front Inside-Out Upside-Down Leeds, according to the Nuttgens book I bagged along with authors offering keys to open secrets of iambic pentameter, how it’s a ball and chain, a waltz – but best, in Žižek’s windsock for the New World Order, Gnostic code imprinted by five feet that lead us to a grail Brown liquefies as Shakespeare melts to decasyllabics like congealed saint’s blood in a Naples shrine. Brown quotes from Philip’s Gospel where it suits to build on Rosslyn Chapel’s premises vast hypophetic labyrinths in the air, yet blind to masons’ mysteries below, who carved among the seven virtues greed with charity being made a deadly sin... The world was made in error Philip wrote – Savonarola, in The Rule of Four (another blockbuster from Oxfam’s shelves) is made to quote ‘the Gospel of St Paul’– does what seems error hide a secret truth? What if ‘Paul’s Gospel’ really did exist? What if it was some long-lost Gnostic text thrown on the Bonfire of the Vanities, so seen there by our zealot’s burning eyes, a road-map to the Holy Grail now ash but seen there by our zealot’s burning eyes? My back-to-back looks on a blind man’s road that draws a straight line north past Wilfred’s city, Shandy Hall then on to Lindisfarne whose monks St Wilfred had been sent from Rome to knock back into line from toe to top, their sinful tops being ‘Simon Magus’ tonsures, named for that gnostic heresiarch a dog denounces in St Peter’s Acts, where Peter raised smoked tuna from the dead, explained his crucifixion upside-down, then how God’s Kingdom might be found on Earth: Make right your left, back forwards, low your high then, in a flash, like Paul, I saw the light through Peter’s apophatic paradox as if from some impacting meteorite that would become Von Eschenbach’s stone grail, the grail that I had thought my writing block: it freed my pen like Arthur’s sword to write this poem backwards, as Da Vinci might.

1 The signal box at Coxwold serves a line that isn’t there, connecting nothing with nothing, thin air with thinner air but its trains of ideas (the phrase is Locke’s) take you to – & – & – past Coxwold signal box. 2 An Irish bull, an English cock, a cat, a mouse, a tree, a clock; an abbey’s stones, its changing faiths, a knife, a book, shapeshifting wraiths; a hobby horse, a maze called Troy, a starry name, Didius’ boy whose meteorite broke the mould of Ptolemy on a Yorkshire Wold. 3 A poem is a meteor Wallace Stevens wrote, one of his lines I often quote or pass off as mine to strike the poet note. A meteor turns to fire in the course of its flight; one crashing to Earth is a meteorite. That is the poem I’m here to write.

‘More binds Walter Benjamin to Walter Shandy than their common first name.’ Samuel Weber, Benjamin’s -abilities Walter Shandy thought nomen est omen, so tried to name his son for a great man but providential stuttering foiled his plan. True art is one, thought Walter Benjamin. Walter Shandy’s clock undoes his heart. Benjamin damned dada for destruction of the aura which distinguishes true art by the means of its own art’s production. Rhyme also reproduces, but in the mind. Dada echoes the sound of the new gun: what the thunder said in World War One, stuttering. A poem is a clock designed to stop, I’ve heard. In this respect, it’s like a man; yet if men and clocks both strike, clocks or poems won’t try to stop another, as, even gently, Walter Shandy’s brother. Benjamin and Shandy share a first name which, oddly, means the ruler of an army; that Weber doesn’t mention this is barmy, but I’m a poem. What I think is all the same

‘A wonderful collection, richly comic and darkly serious in tone... the irresistible force of Duhig’s intellect meets the immovable object of Sterne’s shores sense.’

Morning Star