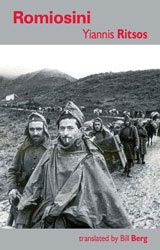

Romiosini

Yiannis Ritsos

Price: £8.95

The word romiosini (ÏωμιοσÏνη) or 'Greekness' derives from the Byzantine idea that the Greeks are the true Romioi, the heirs of the Roman Empire. For hundreds of years under the Turkish occupation the flame of romiosini was kept alive in codes of honour, loyalty, bravery, love of the land, religious devotion and patriotism. For the Greek poet Yiannis Ritsos, the Greek Partisans of EAM/ELAS in the Second World War were the heroic heirs to the romiosini of the mountain klephtes, the medieval epic hero Digenis Akritas, and the revolutionaries who fought against the Turks in the 1820s. First published in 1954, Romiosini was later set to music by Mikis Theodorakis. This is the first time the poem has been published in book form in English.

ΤÏάβηξαν á½Î»ÏŒÎ¹ÏƒÎ¹Î± στὴν αá½Î³á½´ μὲ τὴν ἀκαταδεξιὰ τοῦ ἀνθÏώπου ποὺ πεινάει, μÎσα στ᾿ ἀσάλευτα μάτια τους εἶχε πήξει ἕνα ἄστÏο στὸν ὦμο τους κουβάλαγαν τὸ λαβωμÎνο καλοκαῖÏι. Ἀπὸ δῶ Ï€ÎÏασε ὠστÏατὸς μὲ Ï„á½° φλάμπουÏα κατάσαÏκα μὲ τὸ πεῖσμα δαγκωμÎνο στὰ δόντια τους σὰν ἄγουÏο γκόÏτσι μὲ τὸν ἄμμο τοῦ φεγγαÏιοῦ μὲς στὶς á¼€ÏβÏλες τους καὶ μὲ τὴν καÏβουνόσκονη τῆς νÏχτας κολλημÎνη μÎσα στὰ ÏουθοÏνια καὶ στ᾿ αá½Ï„ιά τους. ΔÎντÏο τὸ δÎντÏο, Ï€ÎÏ„Ïα-Ï€ÎÏ„Ïα Ï€ÎÏασαν τὸν κόσμο, μ᾿ ἀγκάθια Ï€Ïοσκεφάλι Ï€ÎÏασαν τὸν ὕπνο. ΦÎÏναν Ï„á½´ ζωὴ στὰ δυὸ στεγνά τους χÎÏια σὰν ποτάμι. Σὲ κάθε βῆμα κÎÏδιζαν μία á½€Ïγιὰ οá½Ïανὸ – γιὰ νὰ τὸν δώσουν. Πάνου στὰ καÏαοÏλια Ï€ÎÏ„Ïωναν σὰν Ï„á½° καψαλιασμÎνα δÎντÏα, κι ὅταν χοÏεῦαν στὴν πλατεῖα, μÎσα στὰ σπίτια Ï„ÏÎμαν Ï„á½° ταβάνια καὶ κουδοÏνιζαν Ï„á½° γυαλικὰ στὰ Ïάφια. Ἄ, τί Ï„ÏαγοÏδι Ï„Ïάνταξε Ï„á½° κοÏφοβοÏνια – ἀνάμεσα στὰ γόνατά τους κÏάταγαν τὸ σκουτÎλι τοῦ φεγγαÏιοῦ καὶ δειπνοῦσαν, καὶ σπάγαν τὸ ἂχ μÎσα στὰ φυλλοκάÏδια τους σὰ νάσπαγαν μία ψείÏα ἀνάμεσα στὰ δυὸ χοντÏά τους νÏχια. Ποιὸς θὰ σοῦ φÎÏει Ï„ÏŽÏα τὸ ζεστὸ καÏβÎλι μὲς στὴ νÏχτα νὰ ταÎσεις Ï„á½° ὄνειÏα; Ποιὸς θὰ σταθεῖ στὸν ἴσκιο τῆς á¼Î»Î¹á¾¶Ï‚ παÏÎα μὲ τὸ τζιτζίκι μὴ σωπάσει τὸ τζιτζίκι, Ï„ÏŽÏα ποὺ ἀσβÎστης τοῦ μεσημεÏιοῦ βάφει Ï„á½´ μάντÏα á½Î»ÏŒÎ³Ï…Ïα τοῦ á½Ïίζοντα σβήνοντας Ï„á½° μεγάλα ἀντÏίκια ὀνόματά τους; Τὸ χῶμα τοῦτο ποὺ μοσκοβολοῦσε Ï„á½° χαÏάματα τὸ χῶμα ποὺ εἴτανε δικό τους καὶ δικό μας – αἷμα τους – πὼς μÏÏιζε τὸ χῶμα – καὶ Ï„ÏŽÏα πὼς κλειδώσανε τὴν πόÏτα τους τ᾿ ἀμπÎλια μας πῶς λίγνεψε τὸ φῶς στὶς στÎγες καὶ στὰ δÎντÏα ποιὸς νὰ τὸ πεῖ πὼς βÏίσκονται οἱ μισοὶ κάτου ἀπ᾿ τὸ χῶμα κ᾿ οἱ ἄλλοι μισοὶ στὰ σίδεÏα; Μὲ τόσα φÏλλα νὰ σοῦ γνÎφει ὠἥλιος καλημÎÏα μὲ τόσα φλάμπουÏα νὰ λάμπει ὠοá½Ïανὸς καὶ τοῦτοι μὲς στὰ σίδεÏα καὶ κεῖνοι μὲς στὸ χῶμα. Σώπα, ὅπου νἄναι θὰ σημάνουν οἱ καμπάνες. Αá½Ï„ὸ τὸ χῶμα εἶναι δικό τους καὶ δικό μας. Κάτου ἀπ᾿ τὸ χῶμα, μὲς στὰ σταυÏωμÎνα χÎÏια τους κÏατᾶνε τῆς καμπάνας τὸ σκοινὶ - πεÏμÎνουνε τὴν á½¥Ïα, δὲν κοιμοῦνται, πεÏμÎνουν νὰ σημάνουν τὴν ἀνάσταση. Τοῦτο τὸ χῶμα εἶναι δικό τους καὶ δικό μας - δὲ μποÏεῖ κανεὶς νὰ μᾶς τὸ πάÏει.

They pushed on, all together, toward the dawn, with the disdain of a hungry person. In their unflinching eyes a star had formed. They were bearing the wounded summer on their shoulders. The troop passed by here with the flags stuck to their bodies, with hard-bitten obstinacy between their teeth like an unripe wild pear, with sand of the moon in their boots, and coal-dust of the night stuck in their nostrils and ears. Tree by tree, rock by rock they passed through the world. With thorns as a pillow, they passed through sleep. They carried life in their dry hands like a river. With each step they gained two yards of sky – to give it back. Up on the lookouts they grew hard as fire-tempered trees, and when they danced in the square, ceilings trembled inside the houses and glassware tinkled on the shelves. Ah, what song shook the summits! They would hold the moonlit pot between their knees, and dine, and suppress the complaint in their heart of hearts as if squeezing a louse between thick fingernails. Who now will bring you at night that warm loaf of bread to feed your dreams? Who will keep company with the cicada in the olive's shade, and not let the cicada be silent – now that the whitewash of noon coats the horizon's entire corral, wiping out their grand heroic names? That ground with its sweet dawn fragrance, the ground that was theirs and ours – their blood – ah, the scent of that ground! And now, how our vineyards have barred their gates! How the light on the roofs and trees has dimmed! Who is there to tell that half of them are under the earth, the other half in irons? Are those all the leaves you get when the sun bids you good morning? Is that the only banner in the shining sky, with these in irons and those beneath the earth? Never mind. The bells will sound their names. This land is theirs, this land is ours. Under the earth, between their crossed hands, they hold the bell-rope. They await the hour, they're not asleep, they're waiting to announce the resurrection. That land is theirs and ours: no one can take it from us.

'a brave and beautiful long poem rendered into English with enormous sensitivity and imagination.'

Tribune

'a wonderfully figurative, lyrical and cadent long poem... Highly recommended.'

The Recusant

‘works at the highest level of poetic brilliance.’

Mistress Quickly’s Bed