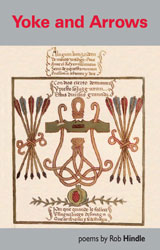

Yoke and Arrows

Rob Hindle

Price: £8.95

In the first weeks of the Spanish Civil War, the radical poet and playwright Federico García Lorca was murdered in Granada by anti-Republican militia. During the early months of the war thousands of Granadinos were killed by these execution squads. Particularly vicious were the Black Squads, many of whom were members of the Fascist Falange. Their symbol was the yoke and arrows (el yugo y las flechas), the symbol of the fifteenth-century Catholic monarchs Isabel and Fernando, who expelled the Moors and the Jews from Spain.

Yoke and Arrows tells the story of those few desperate weeks in 1936, following Lorca's journey from Madrid and a life of celebration and creativity to his pre-dawn death in the mountains above Granada. It also contemplates the parallels between atrocities and acts of retribution across cultures and histories and asserts the responsibility of poetry to bear witness to violation and cruelty in our own violent age.

Yoke and Arrows tells the story of those few desperate weeks in 1936, following Lorca's journey from Madrid and a life of celebration and creativity to his pre-dawn death in the mountains above Granada. It also contemplates the parallels between atrocities and acts of retribution across cultures and histories and asserts the responsibility of poetry to bear witness to violation and cruelty in our own violent age.

18 July, 1936 The guardia props a radio on the window-ledge and the men settle under it. They look at the dust around their boots, the gaunt hides and bones of the sierra stretched into the morning. Going out to the fields there are storks across the empty river. The young have fledged and are bigger than their mothers, but they tread as if mines lie buried in the rush beds. The feast-bells sound across the Vega. It is the day of San Federico, the church filled with flowers and the scent of flowers; and the talk is of Morocco, Franco, the army on the streets of Sevilla.

Women gather at the gaol door with their baskets, jaws and knuckles clamped with fear. Enrique the butcher's son pokes under the linen, bread, cheese, oranges, a clean shirt. Sweat makes stubble on his round face. He nods, looking over Angelina's head, over the town roofs towards the cane fields. They pass into the corridor, footsteps flitting like bats: here is the gaoler, rattling his keys, whistling, eyes bright with the morning's dead.

Members of the Black Squad, assigned to La Colonia to execute the prisoners, are in the upper room, listening to those locked up below. It is some time before dawn. Dark as witches, eyes flickering round the stove, they sit with their legs splayed out straightly, supping cocido. Spoons clack on the tin bowls; one slurps, one spits. The night goes quietly. In the stove's red cowl the fire collapses a little: a brief yellow light jumps into the room, shocking the men's faces, glistening teeth and tongues. Through the floorboards come voices like the voices of the damned, singing lullabies and songs of the country.

A night theme In the house they hide from the stars. The night is in ruins. In the house a dead child lies, a dark rose clustered in her hair. Six nightingales weep for her at the window bars. The men are sighing the truth with their guitars.

'beautifully conjures up the disintegrating world of Federico Garcia Lorca'

Tribune

'a feather in the cap for Smokestack.'

The Recusant