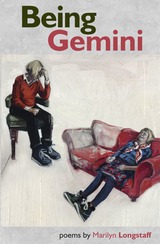

Being Gemini

Marilyn Longstaff

Price: £7.99

Born under the star sign Gemini, thrust into an adult secular world from an unquestioning faith background, Marilyn Longstaff lives somewhere between the miraculous, the magical and the everyday. Being Gemini is a book about the two sides of everything – lockdowns, ageing, deafness, politics and bereavement – and learning to be ‘neither one thing nor the other.’

Cover Image: details from Brechtian Gestures: Marilyn, 2022 © Fiona Crangle

Cover Image design: Pat Maycroft

Author photograph: John Longstaff

13 January 2022 Your birth – I wasn’t there I only have reportage. You came in camouflage, firstborn of twins – identical.

(i) 13 January 2022

Tiny person

we met you

for a little while

minute perfection

in your crystal cave

enshrined in love

how glad we were

to greet you

wish you could have stayed

a moment longer

but thank you

for the time you came to bless our lives.

(ii) 17 January 2022

Not for you an undramatic exit:

nestled in your mother’s arms

you took your leave,

Wolf Moon huge in January sky.

Now we are left to grieve. We drive home over Stainmore, a month to the day, Joseph, that we said goodbye and we drove the same route under the magical light of Wolf Moon rising. This time, Snow Moon appears, pops up above the hills, orange, huge, such a shock in the dark, I almost leave the road from staring. The temperature’s dropping, enough to trigger gritting as we listen to red warnings of Storm Eunice – tomorrow she’ll come. But Oliver, this is your event, your second full moon, and today, you are five weeks old and we have been allowed to see you again, touch your lovely warm and perfect skin. Can such a tiny person know his own mind, play up, show disapproval? What we see and what we know, Oliver, is that you have you own forms of communication. We take note.

I measure your progress in moons, Oliver, miracle baby, born at 22 weeks: 400 grams. You weren’t expected to survive. Your twin brother Joseph didn’t. He died at four days old, when Wolf Moon was full. But you snuck in, hung on, keeping a low profile: no expectation, no expectation. You had the moon in your sights, weathered Snow Moon, Worm Moon, holding on for Easter: first Sunday after the full moon after the vernal equinox. I used to teach this, had a sort of quiz, a formula for kids who finished all their work, to calculate the date for as many years as it took the bell to ring. And you’re still here – Pink Moon, a resurrection. A triumph of medical science and I don’t devalue that, but you are a magic baby, more than a miracle of nature.

Lunar Eclipse I missed it. Hardly surprising. 4 a.m. Heavy snoring. And thick cloud covering for those awake who hoped to see it. The garden is awash with pink and lilac, and today we celebrate your official birth date. You were never planned to be a Winter baby, a child of late Spring who couldn’t wait. But you’ve made it through to another full moon and soon, you can see the world outside a hospital ward. And what a time you’ll have.

Not quite a pound of sugar you carried no weight of expectation just a whisper of ‘maybe’ but ‘probably not’. The weight of evidence came down on 5% to zero so the flutter of ‘possibly’ like an imperceptible wisp of voile fell still as we held our breath and waited minute by minute hour by hour day by night and day month aer month each with its new jolt of heavy fear at every monitor bleep, the wavy lines as you swing from OK to dangerous. And as you grow, gain weight, although we know, and say, ‘Not out of the woods yet’ the harder it is to measure the weight of our hope.

Surviving twin, identical brother: he has his mother’s chin, his father’s toes, and if you catch him in a certain pose, he has his Grandma’s nose, poor speck. And when we look at him, we see the other.

We drive through biblical rain, a second baptism: your first, at 3 days old, the hospital chaplain saving you from limbo – but you didn’t go. And so, today we fetch you home, tiny as a tiny newborn. And at last, we get to see you in the flesh, hold you.

It catches you, not at that moment – paddling for the first time on Scarborough sands with your tiny son, walking behind him holding one of his hands held high, his other arm outstretched for balance; full of delight: his and yours, at new sensations – but later, studying the photograph captured on his mother’s phone, seeing the other – mirror image reflected in the water – imagining, remembering his twin brother.

‘Marilyn Longstaff’s straight talking tone and her understated and deceptively throw-away phraseology confronts the down-to-earth banality of ordinary moments. The poems here drill into lived experiences, anthropomorphisms, contemplations and imaginings in an exploration of physical, social and emotional boundaries, only to subvert them, open them up to a brief instance of pan-temporal compression across history and memory. They subtly pull the rug from under the reader’s feet to reveal a sudden, unsettling swell of psychological vertigo. Longstaff writes powerful unadorned poetry of resilience, resistance and resolve.’

Bob Beagrie

‘Marilyn Longstaff has a unique perspective, combined with a sharp eye for detail which is beautifully realised in these fierce, unflinching poems which find joy and disappointment, in not always equal measure yet move forward, restless and questioning towards whatever comes to haunt us and what remains after us.’

Jack Caradoc