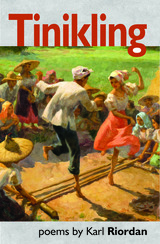

Tinikling

Karl Riordan

Price: £7.99

For the last five years, Karl Riordan and his Filipino wife Jeni have been forced to live thousands of miles apart because of the UK government that expects him to raise £22k to ‘sponsor’ her. Tinikling is a book about love, geography and learning to pick your way through the hurdles and traps of a relationship while navigating the ‘hostile environment’ of the UK immigration system. It’s a book about long-distance intimacy and the short distances between life in working-class Manila and the South Yorkshire ex-mining communities where the author grew up. Taking its title from a traditional Philippine folk dance, Tinikling choreographs a complicated dance between love, racism and bureaucracy.

Cover image: Fernando Amorsolo, The Tinikling Dance Painting

Author photo: Jennifer V. Servino

The small tear in my faded, ex-German postal workers jacket that snagged on the nail that held the string that held the lighter at the door for single cigarette buyers in Tatay Nick’s sari-sari store a week before our marriage. I shovelled my palm into calamansi like searching for the winning bingo ball, two I stole to flavour the Ginebra we might drink together that early morning. His recipes passed on to grandchildren massaged into their palms: adobo, laing, ginataang libas from leaves off the tree planted at the gate – a seedling brought back from Bicol region that now hues the loppy, tawny, dog waiting to be walked. On the living room rug he slept early, curled into a question mark, snoring through a western – the stagecoach chased by arrows on the flickering black and white screen before the market run in the dented Carter van. Only his name above the store exists, now they play mahjong on the green baize table, clacking into the night, sipping shorts. In the yard’s swelter his dogs sniff and yelp. I couldn’t leave without mentioning the cats. The one that followed us in a procession up to the sepulchre, that clammy afternoon. Marmalade smudged, ribs like a rack of knives, it sat beside us whilst we prayed. Another at the wedding-do as we toasted, I felt a figure of eight shift around my shins, then at the last song it made itself seen.

The waiters are scraping Christmas stickers off the window of the roadside café. Adel is our friendly server today, somewhere in her fifties, a missing tooth which she tries to cover with her notepad. In-between balancing plates of food she damp-dusts figurines of the magi removed from the belen with fairy-lights and lined-up on the counter to be wrapped. A table of thirteen are clinking glasses while their teen punctuates the celebration electrocuting mosquitos with swat racquet. The TV reporter tells us: that light rains are to dampen The Black Nazarene procession. A couple overheard near the banyo, Children are part of society, we could always adopt. A scooter rider places his helmet opposite on the table for two, he drowns his bangus in suka. We count out a tip for Adel and leave, notice the empty space in the crib.

We stand on the kanto waiting for a tricycle. The mangos are ready to drop, for the villagers to pick-up. We were just unmarried then, clasping hands within the week. Scent of fruit ripening amongst clothes, unpacking my suitcase.

I pull from my wardrobe your dad’s barong, hang it – shoulders and all – from the door casing, billowing and twisting in the wind, the sleeves reach out a hand. Then I tugged at my cuff in company of godparents to keep tattoos concealed. A long drive to the party in Batangas like the Beverly Hillbillies, teaching me to count and days of the week: isa, dalawa, tatlo... Cooks having a crafty smoke at the stove, turning Cebu lechon over a pit of coals and the pig is smiling at his fate, basted in his toffee-coloured glaze. There’s a private chapel strung in lights, a life-size plastic Jollibee looks on. The men in the group drink two fingers of Emperador brandy – they call Empi and point with their lips at the bottle to hand it around the circle. You’re laid on your back like Huck Finn only a big toe twitching like a stub of ginger. We are sat at the table waiting for food, you mention your fondness for Glen Campbell ‘I hear you singin’ in the wire.’ I’m chewing on a something going nowhere. We are planning to become family and it’s more photos stored on a phone to be shared online with OFWs. In Sheffield, I am pulling creases from your barong I may wear tomorrow – a tang of smoke wafts, catches my throat.

Finding a way into this poem, tricky as packing a balikbayan box sent back from OFWs. You see them on the conveyor belt the globe squeezed into a square from diasporic addresses of the Filipino spread their kababayans forced to cross oceans, to provide for their families. Ate Jen working the NHS frontline, Kuya Don in the Middle East, or Erika cleaning in Barcelona. All watch siblings grow via a phone screen, or bedtime stories in the afternoon. Boxes are filled with candy, letters, books, and tins of Spam. Cast off clothing with life still in them, or basketball vests and baseball hats. On my return to Metro Manila I am weighing scales with pasalubong. We will have a home welcoming meal with cousins hardly recognisable. Firstly, I pick out my old Dickies shirt, a cousin in my pair of combat boots, my checked shirt on my aunt – it’s my personal ukay-ukay store. Then my Levi’s 501s on my lolo that knock ten years off him, the amount of time we have lost.

The above named are to be assessed by the U.K. Decision Making Centre. Please provide the following documents: your wedding and family photographs. Will they look into our eyes, or at a certain way of holding hands to point out something not ringing true? And then the transcripts of conversations, will they twist and frame what was spoken? But what about what was not said? We decide not to mention the priest who wore trainers underneath his vestments, only photographed from the waist up.

A taxi driver from across the way agreed a price to take us on a tour. His notched face and loosened tongue, told us about – ‘a vast and thoughtless head of concrete looked down from shrubs over the land, the wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command. Thirty metres high they built his greased quiff, two years ’til completion, the year of 1980. It’s claimed the Ibaloi were forced to sell their land for low, low prices. They drained blood from pig and carabao and flooded the bust in an exorcism. This followed the ’86 People’s Revolution where placards read: Suko Na! Talo Ka Na! Marcos Layas Na! In short, You’ve lost! Marcos run away! Then just after Christmas in 2002 treasure hunters or New People’s Army did what you see today.’ Did the dynamite make Marcos sing? Were they like the Numskulls whispering into the President’s ear? His brains are now blown inside out, they’ve left him barely a frown. You’ll have heard his words aired by satellite, under the shadow of Imelda, her sculptured hair, heels perched in stilettos. Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Our tour guide fans himself, with a waft of banknotes slotted between his fingers and thumb, he sneezes three times. A long toot at the horn as we sound off into a wheelspin leaving enough dust to pack the nostrils like snuff.

It was when you leaned over and whispered, after our meal, the stick dance started, and you taught me the word tinikling. I could feel the tamp, tamp of bamboo poles rise from floor to white flab of my thighs and you’d never seen a dancer snapped like a rabbit in a gin-trap. We were on a two-for-one deal, I wondered if I should sell my watch, strapped to the inside of my wrist – ticking. Your legs stiff as chopsticks, under the table cross around mine which is when I knew. We sit upright, two chess pieces – king and queen.

‘Karl Riordan’s poems take us into language-worlds, the close hot-house of the family, the affects and wit of working-class social scenes, the global south witnessed through transnational love, the three- and four-beat lines scoring out a life along the heart, with superbly voiced, compacted textures that live and breathe, each poem focussing with powerful charm upon the otherness of the real.’

Adam Piette

‘Poetry of truth and rage. Karl Riordan dares to speak of hope and love in a world divided by borders against a back drop of 21st-century crises on so many fronts including hard-right opportunism with its historical echoes. This splendid collection makes us truer to ourselves and those around us.’

Stephen Sawyer

‘minimal and free-flowing.’

Salzburg Poetry Review