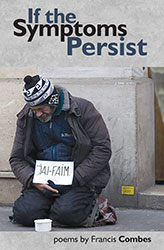

If the Symptoms Persist

Francis Combes

Price: £8.99

If modern French poetry began with Rimbaud’s observation that ‘je est un autre,’ Francis Combes believes that poets should now say, ‘je suis tous les autres’. The author of fifteen books of poetry, including La Fabrique dubonheur, Cause commune and La Clef du monde est dans l’entrée à gauche, Combes has also published two novels and, with his wife Patricia Latour, Conversation avec Henri Lefebvre and Le français en liberté – Frenglish ou diversité. He has translated several poets into French, including Heine, Brecht, Mayakovsky and Joszef. ]He runs the radical publishing cooperative, Le Temps des Cerises, directs the poetry biennale in Val de Marne and was for many years responsible for putting poems on the Paris Metro.

‘Poetry,’ argues Combes, ‘does not belong to a small group of specialists. It arises from the everyday use of language. It is a way of keeping your feet on the ground without losing sight of the stars. It is at the same time the world’s conscience and its best dreams; it’s an intimate language and a public necessity.’ Drawing on the tradition of Hugo and Aragon, the idea of une poésie d’utilité publique runs through Francis Combes stunning new collection, frompoèmes sans domicile fixe to poèmes moraux et politiques. It is a book about poverty, homelessness, inequality, racism and the endless wars of the twenty-first century. It’s a book of gentle humour and savage irony. It is that rare thing, a collection of poetry that is both useful and necessary.

Un jeune mendiant croisé dans le métro, sur un bout de carton accroché à son cou avait écrit ces mots : ≪ Comme la forêt en feu crie vers l’eau de la rivière je m’adresse a vous : Donnez-moi SVP quelque chose à manger. ≫ Et, semble-t-il, des gens donnaient. (Ce qui tendrait a démontrer l’utilité dans nos sociétés de la poésie.)

A young beggar met in the metro had written these words on a piece of cardboard hung round his neck; ‘As the burning forest shouts towards the river’s water I appeal to you: Please give me something to eat.’ And it seems People were giving. (Which would tend to point to the usefulness of poetry in our societies.)

À la sortie du grand magasin un homme corpulent (barbe rousse, tête de moujik ou de pirate des Caraïbes) est agenouillé sur son sac au milieu du trottoir. Il ne prie pas Dieu mais l’humanité qui passe dans tous les sens devant lui. Quelques humains donnent; peu nombreux (juste assez pour qu’il persévère dans son activité)… Mais la plupart de ceux qu’ils prie font comme Dieu: ils ne lui pretent aucune attention.

At the exit to a department store a corpulent man (red beard, head of a Moujik or Caribbean pirate) is kneeling on his bag in the middle of the pavement. He isn’t praying to God but humanity which passes in every direction before him. A few people give him something not many (just enough for him to keep going) But most of those he appeals to do as God: they pay him no attention.

Dans le ventre de Paris, sous le Forum des Halles, juste à côté du passage souterrain qu’empruntent les automobiles, le long de la voie rapide, un homme a installé son canapé, sa télé, son poste de radio et un écran d’ordinateur. Là, il est a l’abri, au chaud, dans les gaz d’échappement. Ici, personne ne le dérange, mais de là où il est il ne voit pas le bout du tunnel.

In the belly of Paris under the Forum des Halles just next to the underpass which no cars take along the fast lane a man has set up his sofa his telly his radio a computer screen. Here, he is sheltered, warm, in the exhaust fumes. Here, no one disturbs him, but from where he is he can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Boulevard de Friedland, à quelques pas de l’Arc de Triomphe, neuf heures trente, un lundi matin. (Quelle est la victoire que l’on célèbre ici ?) alors que le flot des voitures s’écoule lentement (ce qui laisse a chacun le temps de regarder) une femme, debout à côté de sa tente igloo sur le trottoir, sa petite culotte sur les chevilles, tournant le dos à la circulation fait, avec un bout de chiffon, sa toilette intime.

Boulevard de Friedland, a few feet from the Arc de Triomphe, half past nine on a Monday morning. (What is the victory being celebrated here?) while the flow of cars passes slowly (which gives everyone the time to look) a woman, standing next to her igloo tent on the pavement, her little knickers around her ankles, her back turned to the traffic carries out with a bit of rag her intimate washing.

A quelques jours de Noël j’ai vu un homme assis sur le trottoir du côté d’Arts et Métiers emmitouflé dans la feuille metallisé d’une couverture de survie offerte, sans doute, par un service social, ou une ONG humanitaire. Sa tête, ronde et noire aux grands yeux hagards seule dépassait de l’emballage doré. Il ressemblait à un cadeau, un pauvre, que la ville se serait offerte. (Noël n’oublie personne).

A few days before Christmas I saw a man sitting on the pavement in the Arts et Metiers wrapped in the metallised leaf of a survival sheet provided, no doubt, by social services or a humanitarian NGO. His head alone round and black with great, haggard eyes stuck out of the golden package. He looked like a present, one of the poor, the city had given itself. (Christmas forgets no one).

C’est là que se tenait Ginka avec les autres, sur le terre-plein battu par le vent de novembre, là où la rue pavée du Débarcadère qui longe la voie ferrée et passe sous le périphérique débouche sur les éxterieurs et devient la rue de la Clôture. C’est là sur le petit terre-plein qu’elle se tenait avec trois ou quatre filles, jeunes comme des lycéennes, tous les jours là, brûlant de la beauté de la jeunesse mini-jupe, insulte à l’hiver flammes fragiles a tous les vents offertes. Ginka, flamboyante chanterelle, rousse, venant de l’est, rêvait de liberté et de se faire un paquet de fric pour flamber à Paris. Mais de Paris, elle n’a connu que ce bout de trottoir battu par le vent où le jour et la nuit debout des heures sans boire et sans manger devant faire ses besoins accroupie sur le sol comme une bête elle a découvert la dure loi de l’offre et la demande, les travaux forcés du libre marché. Un employé de la déchetterie voisine l’a retrouvée au milieu des immondices et des préservatifs entre des bouteilles vides et un pare-choc brisé, dans les broussailles, derrière le grillage à moitié défoncé au-dessus de la voie ferrée tuée de vingt coups de couteau puis abandonnée sur un vieux matelas. (Le monde n’a plus de frontières. C’est une décharge sans rivage ou dansent des flammùches et fleurit l’aster.) Sur le grillage, pendant quelques jours est restée accrochée une gerbe, couronne pour Ginka qui se voyait top-model ou bien reine de beauté, Ginka qui ne fut pas même reine de sa propre vie.

It was there Ginka was standing with the others, in the lay-by battered by the November wind there where the cobbled street of Debarcadere which runs by the rail line and under the peripherique opens onto the city’s limits and becomes the street of la Cloture. It’s there in the little lay-by she stood with three or four other girls young as high school pupils, there every day burning with beauty and youth a mini-skirt insulting the winter fragile flames offered to every wind. Ginka, flamboyant chanterelle, red-headed coming from the East dreaming of freedom and of making a shed-load of money to burn in Paris. But all she’s known of Paris is this bit of pavement battered by the wind where day and night standing for hours without eating or drinking having to crouch on the ground like an animal she discovered the hard law of supply and demand the forced work of the free market. A worker from the neighbouring dump found her in the middle of refuse and contraceptives between empty bottles and a broken bumper in the bushes behind the half-caved in radiator grill above the rail line killed by twenty stabs then abandoned on an old mattress. (Th world no longer has borders. It’s an outlet without limits where sparks dance and the aster flowers.) On the grill for several days has remained a sheaf of flowers, a crown for Ginka who saw herself as a top model or beauty queen, Ginka who was not even queen of her own life.

‘Francis Combes n’y consent pas! Faire parler ce qui est senti de ce monde est sa belle querelle. C’est à nous, lecteurs, de se confronter à leur corps pour en tirer troubles, leçons et actions!’

L’Humanité

‘humorous, straightforward, engaging, entertaining... the poems fizz with anti-capitalist sentiment.’

Manchester Review of Books

‘excoriating in his criticisms of capitalism... incisive and devastating, he exposes some of the darkest aspects of the lives of homeless people in France.’

Socialist Review

‘the poems fizz with anti-capitalist sentiment, but always with a sense of humour, a spirit that we can crack this blank grey wall of indifference with language, and with simple language.’

Manchester Review of Books