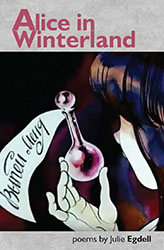

Alice in Winterland

Julie Egdell

Price: £7.95

Growing up in Whitley Bay, Julie Egdell never knew how much she had in common with Lewis Carroll’s Alice. But when she went to work in St Petersburg she discovered that she was the spitting image of the Russian version of Alice – not Tenniel’s blonde school-girl, but the dark-haired ‘Alisa’ of Soviet illustrated children’s stories, sarcastic and cruel and very Russian. A new city, a new language and a new identity. What could possibly go wrong?

Alice in Winterland is the story of a strange and subversive wonderland, of a worm who thinks he is a caterpillar and the Baba Yaga who became a witch. It’s a book about life in post-Soviet Russia, mad hatters, tears and temptations. It is a story of exile, heartbreak, loneliness and longing, about falling down a cultural and linguistic rabbit hole.

Author photo credit: Hannah Halbreich

I fell down the rabbit hole. Now I wear the rabbit as a coat. Its skin smells salty and ancient. Its fur a gift for the long winter. In wonderland they call me Alisa – only Alice here is nasty, not nice. Black hair, strong cheekbones, acid tongued and scowling. She is carved from the permafrost. Eyes like chipped sapphires. Выпей меня on the vodka bottle – the drink makes you stronger and healthier, or shrinks and blinds you, depending on the brand. In wonderland cats don’t grin and the caterpillar is a sick worm sending tasty smoke rings dancing in karaoke bars that never sleep. Eшь меня. I eat Soviet donuts in grandma’s kitchen. Everything tastes of survival. What is this world? Vertical villages hide soviet complacency mixed with Slavic pride. The tower block reads Настя ятебя Nastya ya tibya lyublu Nastya I love you. Each floor a different letter. How did he do it – scale the side of the block on a rope? And why? Had Nastya died? Maybe a fight? Did Nastya feel the same? Alongside blocks monuments to capitalism – MEGA malls and McDonald’s. And then, further out, dachas built by hand from forest wood in the war. Embarrassments to nouveau Russia’s mansions. The villages of Piter a playground for the rich. Traffic jams – Lada’s next to Land Rovers. In wonderland we feed birds and squirrels by hand, grow our own in the absence of currency – we know that supermarket stuff comes from Chernobyl. We pick mushrooms and berries – grandma knows which don’t kill you or send you crazy. Every year in Spring police extract cars and people from the Neva – those who went ice fishing wound up being the catch. In wonderland I am a stranger. I drink tea from china cups in tiny apartments shared by big families, without choices. In wonderland snowflakes are innocence. Dust and dirt homeless and limbless vanish in the snow. It washes away the past, and changing, it rests. Canals freeze over the long winter grips. In wonderland there’s no evil queen, but years of evil kings. Deformed foetuses, pickled in vodka, line palace walls. Whispers of an evil that never sleeps.

I am asked кто ты? Who are you? But can’t remember. First they call me Yulia, then Alisa – on account of my being English and dark haired. In this Soviet city there were no childhoods watching capitalist Disney. They tell me I am just like her. In the absence of you, my imagined paradise, there can only be drowning of voices. I have lost hope. You cut my hair, I bought your clothes. You sang to me, I read to you. You rolled the joints, I poured the drinks. Usually we said what we meant. But sometimes we didn’t. You went wherever I led and I left the breadcrumbs of my heart in all our places in place of your passion. But later I couldn’t find my way back – you had eaten them all.

Sweet Alisa all grown up. Adulthood is so destroying. A plastic surgeon you spend your days telling patients it’s dangerous to talk. Spend your nights eating 99 Kopeck ice cream with your daughter. Dreaming of a land where husbands could be at home. You remember childhood summers at your grandfather’s dacha in the Ukraine. Collecting warm eggs at dawn, the bitterness of berries ripe from the sun. One day he dies, suddenly, and you, at 33, notice childhood is gone. You cried that day. Learning English because you too believe there is a better life, a better place. You fall in love with me – the English Alice of your childhood. Because you still believe in wonderland.

A young scientist who works in a cafe decides upon a theme – Alice in Wonderland. She has long, blonde hair emerald eyes which hurt what they touch. A hidden smile. She thinks I am Alice. She falls in love with me and England, but gets to know us better. She borrows a white rabbit. Dresses as the Disney Alice, the inventor of a dreamland in a Petergof cafe, but is disappointed – Petergof ’s MEGA mall shoppers don’t know Disney Alice. Where is your dark hair? Your sarcastic smile? Your sharp fringe? Your white dress?

‘These Alisa poems give Julie Egdell the means of exploring her life beyond the North-East, poems sent back as postcards from the edge of language, from economic and cultural exile, examining language and the discourses of the self through geographic shift and the forbidden look over the shoulder.’

Bob Beagrie

‘an unflinching writer with an unnervingly clear eye for the telling detail or unsettling truth that digs under the surface of the everyday, her willingness to journey to the edges of both domestic and on-the-road experiences and her toughness with language has given her an original voice – female, imaginative, erudite but with working class authenticity that really makes for poetry with an edge. She is a significant poet.’

Andy Willoughby

‘startling, original and very unsettling... a collection to appreciate and a poet to watch.’

The Sentinel