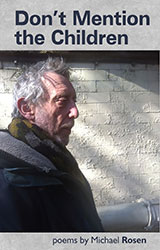

Don't Mention the Children

Michael Rosen

Price: £8.95

Michael Rosen is one of our best-loved and writers for children. He has written and edited over 140 books, including contemporary primary-school classics like Mind Your Own Business, Wouldn’t You Like to Know, Mustard, Custard, Grumble Belly and Gravy, You Tell Me, No Breathing in Class and Quick Let’s Get Out of Here. You Can’t Catch Me! won the Signal Poetry Award. We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury, won the Smarties Prize.

Rosen’s poems for grown-ups are less well known, and Don’t Mention the Children is his first collection since Selected Poems (Penguin) in 2007. Fans of his children’s books will enjoy the way these poems combine the silly and the sinister to catch the surrealism of everyday life, somewhere between Jacques Prévert, Ivor Cutler and Adrian Mitchell. Few poets writing today can move so effortlessly between childishness and childlike seriousness. But at the heart of the book is a remarkable series of poems about anti-Semitism, Fascism and War, connecting the contemporary world – UKIP, Marine le Pen, Palestine (the title poem refers to the refusal of the Israeli broadcasting authorities to mention the names of children killed during the Israeli shelling of Gaza in 2014) – to the lives of Rosen’s parents and grandparents, the General Strike, the Battle of Cable Street, Vichy, Auschwitz.

Cover photo: Emma-Louise Williams

a story for Holocaust Memorial Day This is about France This is about Germany This is about Jews. This is not about France This is not about Germany This is not about Jews. In the family they were always the French uncles, the ones who where there before the war, the ones who weren’t there after the war. The family said that one of them was a dentist and the other one mended clocks and that’s it. Not quite it. There was a street that the relatives here and in America kept saying, which was: rue de Thionville, rue de Thionville. And places in France: Nancy, Metz, Strasbourg and one of the brothers was Oscar and the other was Martin. And that was it. Though Olga, in America nearly as small as a walnut, said that she used to write letters to them to learn how to write French. And Michael here in England said that he used to write letters to them to learn how to write French. And that was it. That’s how it was, they said. Michael knew how it was. His mother was the sister of the French uncles and she waved Michael goodbye when he was 17 and that was the last he saw of her. And that was it. But I wouldn’t let it go and I Started looking for the rue de Thionville and at an airport I met a guy who came from Metz and he said he would go to the Mairie, the town hall, and look up Oscar and Martin, rue de Thionville and he did or says he did and he wrote back to say he didn’t find anything. And that was that. But then Teddy in America wrote to say that some letters have turned up, a son of a brother of a mother or something has got letters from 1941. And they’re from Oscar, and they’re from Michael’s father And oh my god they’re asking for help, they’re letters to their brother Max , (Look, I know the names won’t mean much to you, I’ve been living with this stuff and I don’t even know why I’ve tried so hard to find out about it, but there were these brothers and sisters, all born in Poland, one of them is Michael’s mother. That’s Stella, she stayed there, married Bernard, there are the ones who went to France that’s Oscar and Martin; there’s Max who went to America along with Morris that’s my father’s father. I know the names.) So when I see the letters I know who they are, Oscar asking Max for help, Bernard asking that money should be sent to Michael who was now in Siberia, Bernard doesn’t know that he’ll never see his son Michael again, and I’m looking at the letters, and there’s an address in France, not rue de Thionville, in Metz or Nancy or Strasbourg. It’s 11 Rue Mellaise, (remember that) in Niort in Deux-Sèvres. The other side of France. And I start to read about how they all fled, everyone fled ‘L’exode’ they called it, the Exodus, everyone fled from the east to the west, and here’s Oscar in the west in Niort Deux-Sèvres...11 Rue Mellaise, (remember the address). I find the house on google, there it is, a shop downstairs a flat above, the French street, the shutters, the grey render of the walls, the kind of place I’ve walked down a thousand times on trips to the country I love to be in, the place I discovered things I couldn’t buy or have in England in the 1960s: ‘jus de pomme’ in big brown bottles, fresh melons, blue vests, ‘espadrilles’, I didn’t even know why it mattered and here was 11 Rue Mellaise, the kind of place I would have liked to have stayed in but this was the address for the last letter any of us have from Oscar. And that was that. But I wouldn’t let go of it, and I started looking for what happened to Jews in Niort, in Deux-Sèvres and I found books which spoke of ‘rafles’, round-ups and a young rabbi who did all he could. But it wasn’t enough and every time I found a book I went to the index to look for the name, Rosen. It’s something I’ve done, looking for my own name, or the name of my brother or father or mother but now I was looking for Oscar or Martin, and then, somewhere I found something that I should have known about but didn’t. ‘Le fichier juif’, the Jewish file, the document or dossier of Jews. In France, there’s a job called ‘Prefect’ and ‘Sub-prefect’, local officials and these prefects and sub-prefects carefully wrote out the names of every Jew, date of birth, place of birth, job, married to...names of children. And there in one of the books was page 1 of the fichier juif for Deux-Sevres. But where was this fichier juif? I wanted to know, I don’t know why, and it seems as if most of the fichiers juifs just disappeared after the war, they just slipped away and would have been lost, vanished. But for some reason a pile of them turned up in a basement of a building and carefully and slowly they had been put together and copied but all I could see was page one. A facsimile of page one. And that was that. But then at the back of a book I found the name of another book: ‘Les chemins de la honte, itinéraire d’une persecution, Deux-Sèvres 1940-1944’, by Jean-Marie Pouplain... The path of shame, the account of a persecution, Deux-Sèvres 1940-1944 and I ordered it. It arrived into a house we were on the verge of moving out of, so there was something temporary and on the move about us at that point, but the book arrived and I pulled off the cardboard packaging and I did what I’ve done before I looked in the index for Rosen and it said, 34, 65, 96,108,197,202,203,205,210,212,213,236,240,244. And I turned to page 34 and there was the fichier juif and number 40, it said, ‘Rosen, Jeschie, né le 23 juin, 1895, polonaise, bonneterie, marié à Kesler, Rachel, née en 1910, 11 Rue Mellaise.’ Some things very right, some things not so right. The name Jeschie, Oh I figured it was a nickname. Jews have Hebrew names and sometimes their Christian names are echoes of the Hebrew names, perhaps he was Oscar because it rhymed with Yehoshua and the Yiddish nickname of Yehoshua was perhaps Jeschie...? But the job, ‘bonneterie’ it means the person who sells clothes in the market. Not a dentist or a clockmaker. And I slowly looked up each number and each page number told what the prefect and the sub-prefect carefully wrote down, how Jeschie and Rachel were given their yellow stars, how they had to pin a sign saying ‘Entreprise Juive’, ‘Jüdisches Geschäft’, Jewish business to their market stall, how everything they owned was taken away from them in a process called ‘aryanisation’. The business was Aryanised...whatever that meant, and there on one of the entries it said that Jeschie was an ‘horloger de carillon’ – a mender of chiming clocks. But what about the last pages? and I turned to the last page numbers – pages 234 and 236, 240 and 245 and Jeschie Rosen was arrested outside of Deux-Sèvres, he seems to have tried to get away, ‘clandestinement’ – secretly, but was picked up somewhere else and then he and Rachel appear on another document, the lists that the Nazis made in Paris of every Jew they put on what the French called ‘convois’ – ‘convoys’ and there they are on convoy 62, leaving Paris on November 20 1943 going to Auschwitz. And when I had read all that, as I stood there with the book in my hand I knew that I was the first person in the family to know all this and it felt like I had to tell everyone and I sat down and started to write a letter to all the relatives which I didn’t finish because I had to go and find out – and I knew where to look – how many people were on that convoy, how long did it take to get to Auschwitz, what happened the moment the train arrived, how many never came back, how many survived. I read: ‘1200 Jews left Paris/Bobigny at 11.50 am on November 20 1943. Arrived Auschwitz November 25, as cabled by SS Colonel Liebenhenschel 1181 arrived. There had been 19 escapees, they were young people who escaped at 8.30pm Nov 20 near Lerouville. In the convoy there were 83 children who were less than 12 years old. Out of the convoy 241 men were selected for work and given numbers 164427-164667 Women numbered 69036-69080 were selected too. 914 were gassed straightaway In 1945, there were 29 survivors – 27 men 2 women.’ I looked over what I wrote before I sent it off to my brother, and to my cousins who would pass it on to Michael and to Max’s son in America – who I haven’t told you is 103 years as I write this. I thought about what kind of war was it, what kind of people was it, who looked at a mender of clocks and his wife and put them in a document, made them wear a yellow star, made them put a sign up on their market stall, took their money away from them, arrested them, put them in a transit camp, put them on a train and sent them to a camp in Poland where they were killed? This is a story about France, a story about Germany, a story about Jews. This is a story that’s not about France, not about Germany, not about Jews. I found these things out in order to know. I found these things out, I know now, in order to tell other people. I found these things out so that Jeschie and Rachel will be known. But in the end I know that the point of them being known is That this is a story not just for them and about them.

the reason why they gave a yellow star to my father’s uncle and aunt the reason why they told them they had to fix a sign saying ‘Jewish Business’ on their market stall the reason why they fled from their refuge in the rue Mellaise in Niort the reason why they took refuge in Nice the reason why they were arrested and transported to Paris, to Drancy, to Auschwitz and to their death is because the officials of Vichy made a ‘Jewish File’ of foreign Jews and gave it to the Nazis at the exact moment that the Resistance was welcoming Jews and was welcoming foreigners and that’s the reason why I am telling you these things Mme Le Pen.

I sometimes fear that people might think that fascism arrives in fancy dress worn by grotesques and monsters as played out in endless re-runs of the Nazis. Fascism arrives as your friend. It will restore your honour, make you feel proud, protect your house, give you a job, clean up the neighbourhood, remind you of how great you once were, clear out the venal and the corrupt, remove anything you feel is unlike you... It doesn’t walk in saying, ‘Our programme means militias, mass imprisonments, transportations, war and persecution.’

‘hilariously funny as well as packing a punch.’

Stride

‘if these poems are unashamedly political, then good!’

Write Out Loud

‘Only an exceptional collection will have the reader buying multiple copies and urging all their friends: “Read this!” This is what I did when I first got my hands on Don’t Mention the Children.’

English in Education

‘This is unmistakeably committed political verse.’

Jewish Chronicle