Epitaphios

Yiannis Ritsos

Price: £8.95

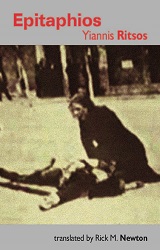

On 10 May 1936 the 27-year old Greek poet Yiannis Ritsos saw a newspaper photograph of a woman weeping over the body of her son, a Thessaloniki tobacco-factory worker killed by police during a strike. Two days later the Communist Party newspaper Rizospastis published a long poem by Ritsos. Dedicated ‘to the heroic workers of Thessaloniki’ and drawing on the sixth-century Greek Orthodox Epitaphios Thrinos, the poem combines Mary’s lament at Christ’s tomb with popular Greek folk traditions of resurrection and Spring to create a universal lament sung by every bereaved mother ‘who sits and mourns on the blood-stained street with her heart flayed, her wing broken.’ Although Epitaphios was banned in Greece for many years, in the 1950s an expanded version of the poem was set to music by Mikis Theodorakis and recorded by Nana Mouskouri. This is the first time Epitaphios has been published in book form in English.

Θεσσαλονίκη. Μάης τοῦ 1936. Μιὰ μάνα, καταμεσὶς τοῦ δρόμου, μοιρολογάει τὸ σκοτωμένο παιδί της. Γύρω της καὶ πάνω της, βουΐζουν καὶ σπάζουν τὰ κύματα τῶν διαδηλωτῶν – τῶν ἀπεργῶν καπνεργατῶν. Ἐκείνη συνεχίζει τὸ θρῆνο της: Γιέ μου, σπλάχνο τῶν σπλάχνων μου, καρδούλα τῆς καρδιᾶς μου, πουλάκι τῆς φτωχειᾶς αὐλῆς, ἀνθὲ τῆς ἐρημιᾶς μου, Πῶς κλεῖσαν τὰ ματάκια σου καὶ δὲ θωρεῖς ποὺ κλαίω καὶ δὲ σαλεύεις, δὲ γροικᾶς τὰ ποὺ πικρὰ σοῦ λέω; Γιόκα μου, ἐσὺ ποὺ γιάτρευες κάθε παράπονό μου, ποὺ μάντευες τί πέρναγε κάτου ἀπ’ τὸ τσίνορό μου, Τώρα δὲ μὲ παρηγορᾶς καὶ δὲ μοῦ βγάζεις ἄχνα καὶ δὲ μαντεύεις τὶς πληγὲς ποὺ τρῶνε μου τὰ σπλάχνα; Πουλί μου, ἐσὺ ποὺ μοὔφερνες νεράκι στὴν παλάμη πῶς δὲ θωρεῖς ποὺ δέρνουμαι καὶ τρέμω σὰν καλάμι; Στὴ στράτα ἐδῶ καταμεσὶς τ’ ἄσπρα μαλλιά μου λύνω καὶ σοῦ σκεπάζω τῆς μορφῆς τὸ μαραμένο κρίνο. Φιλῶ τὸ παγωμένο σου χειλάκι ποὺ σωπαίνει κ’ εἶναι σὰ νὰ μοῦ θύμωσε καὶ σφαλιγμένο μένει. Δὲ μοῦ μιλεῖς κ’ ἡ δόλια ἐγὼ τὸν κόρφο, δές, ἀνοίγω καὶ στὰ βυζιὰ ποὺ βύζαξες τὰ νύχια, γιέ μου, μπήγω. Thessaloniki. May 1936. In the middle of the street a mother sings a dirge over her slain son. Waves of demonstrators – the striking tobacco workers – crash and resound around her. She continues her lament: My son, the child from my womb, dear heart of my own heart, The nestling in my humble yard, my desert’s only bloom. How can your eyes be shut so tight and you not see me sob? Why don’t you stir, why don’t you hear the bitter words I cry? My son, you’d cure my every grief and fill my every void. You’d fathom every thought and fear that ranged beneath my brow. But now, why don’t you breathe a word? Why don’t you comfort me? Can’t you divine the dreadful wounds devouring my heart? You used to bring me water in the cupped palm of your hand. Why can’t you see me lashed about and trembling like a reed? Here in the middle of the street I let my white hair down And shroud the wilted lily of your fair and comely face. To your sweet lip I give a kiss. It’s ice-cold and dead still, As if it were enraged with me, so firmly clenched and tight. You do not speak, but look at me: I open up my blouse And plunge my nails into the breasts that nursed you as a babe.

Κορώνα μου, ἀντιστύλι μου, χαρὰ τῶν γερατειῶ μου, ἥλιε τῆς βαρυχειμωνιᾶς, λιγνοκυπαρισσό μου, Πῶς μ’ ἄφησες να σέρνουμαι καὶ νὰ πονῶ μονάχη χωρὶς γουλιά, σταλιὰ νερὸ καὶ φῶς κι ἀνθὸ κι ἀστάχυ; Μὲ τὰ ματάκια σου ἔβλεπα τῆς ζωῆς κάθε λουλούδι, μὲ τὰ χειλάκια σου ἔλεγα τ’ αὐγερινὸ τραγούδι. Μὲ τὰ χεράκια σου τὰ δυό, τὰ χιλιοχαϊδεμένα, ὅλη τὴ γῆς ἀγκάλιαζα κι ὅλ’ εἴτανε γιὰ μένα. Νιότη ἀπ’ τὴ νιότη σου ἔπαιρνα κι ἀκόμη ἀχνογελοῦσα, τὰ γερατειὰ δὲν τρόμαζα, τὸ θάνατο ἀψηφοῦσα. Καὶ τώρα ποῦ θὰ κρατηθῶ, ποῦ θὰ σταθῶ, ποῦ θἄμπω, ποὺ ἀπόμεινα ξερὸ δεντρὶ σὲ χιονισμένο κάμπο; Γιέ μου, ἂν δὲ σοὖναι βολετὸ νἀρθεῖς ξανὰ σιμά μου, πάρε μαζί σου ἐμένανε, γλυκειά μου συντροφιά μου. Κι ἂν εἶν’ τὰ πόδια μου λιγνά, μπορῶ νὰ πορπατήσω κι ἄν κουραστεῖς, στὸν κόρφο μου, γλυκὰ θὰ σὲ κρατήσω. You were the joy of my old age, my crowning pride, my rock, My shining sun in winter’s depth, my cypress slim and tall. How can you leave me all alone to drag myself in pain, Bereft of light, without a crumb, without a drop to sip? Life’s every flower I could see, but only through your eyes. I’d greet each morning with a song, but only through your lips. With your two arms, which I caressed a thousand times and more, I held the earth in my embrace, and all the world was mine. From your own youth I took my youth and chuckled to myself. Old age evoked no dread in me. I disregarded death. And now, what can I hold on to? Where can I go or stay? I’m left alone, a withered tree, lost in a snowy plain. My son, if it’s not possible to come back close to me, Then take me with you, my sweet boy, and keep me company. Although my legs are weak and thin, I’ll walk along your side. And if you tire, I will clutch you sweetly to my breast.

Νἆχα τ’ ἀθάνατο νερό, ψυχὴ καινούργια νἆχα, νὰ σοὔδινα, νὰ ξύπναγες γιὰ μιὰ στιγμὴ μονάχα, Νὰ δεῖς, νὰ πεῖς, νὰν τὸ χαρεῖς ἀκέριο τ’ ὄνειρό σου νὰ στέκεται ὁλοζώντανο κοντά σου στὸ πλευρό σου. Βροντᾶνε στράτες κι ἀγορές, μπαλκόνια καὶ σοκάκια καὶ σοῦ μαδᾶνε οἱ κορασιὲς λουλούδια στὰ μαλλάκια. Γιὰ τὸ αἷμα ποὔβαψε τὴ γῆς ἀντρειεύτηκαν τὰ πλήθια, – δάσα οἱ γροθιές, πέλαα οἱ κραυγές, βουνὰ οἱ καρδιές, τὰ στήθεια. Ἔσμιξε ἡ μπλούζα τὸ χακί, φαντάρος τὸν ἐργάτη κι ἀστράφτουν ὅλοι μιὰ καρδιὰ – βουλή, σφυγμὸς καὶ μάτι. Ὤ, τί ὄμορφα σὰν σμίγουνε, σὰν ἀγαπιοῦνται οἱ ἀνθρῶποι, φεγγοβολᾶνε οἱ οὐρανοί, μοσκοβολᾶνε οἱ τόποι. Κι ὅπως περνᾶν. λεβέντηδες, γεροὶ κι ἀδερφωμένοι, λέω καὶ θὰ καταχτήσουνε τὴ γῆς, τὴν οἰκουμένη. Κ’ οἱ λύκοι ἀποτραβήχτηκαν καὶ κρύφτηκαν στὴν τρούπα – μαμούνια ποὺ τὰ σάρωσε βαρειὰ τοῦ ἐργάτη ἡ σκούπα. Ὤ, ποὖσαι, γιόκα μου, νὰ δεῖς, πουλί, ν’ ἀναγαλλιάσεις, καί, πρὶν κινήσεις μοναχό, τὸν κόσμο ν’ ἀγκαλιάσεις; O, how I wish I had the deathless water, a new soul, To give you and to wake you up for just one moment more, For you to see your dream come true, to take joy and delight, To see it standing next to you, complete and full of life. The balconies and markets roar, the streets narrow and wide, While young girls pick spring flowers and strew petals on your hair. The crowds have grown courageous from the blood that’s stained the earth – With groves of fists and seas of shouts, high crests of hearts and chests. The worker joins with soldier now, the khaki with the blue. A single heart shines in them all – one will, one pulse, one gaze. O, what a lovely sight it is when people join in love: The skies above blaze with their light, the lands around smell sweet. And as these young men make their way, strong in their brotherhood, They look like they can take the world and all the universe. The wolves have made a full retreat and slunk back to their holes, Like ants swept up and whisked off by a common workman’s broom. Where are you, son, to see all this and revel in the sight? Embrace the world before you leave. Then, take your lonely path.

Γλυκέ μου, ἐσὺ δὲ χάθηκες, μέσα στὶς φλέβες μου εἶσαι. Γιέ μου, στὶς φλέβες ὁλουνῶν, ἔμπα βαθιὰ καὶ ζῆσε. Δές, πλάγι μου περνοῦν πολλοί, περνοῦν καβαλλαραῖοι, – ὅλοι στητοὶ καὶ δυνατοὶ καὶ σὰν κ’ ἐσένα ὡραῖοι. Ἀνάμεσά τους, γιόκα μου, θωρῶ σε ἀναστημένο, – τὸ θώρι σου στὸ θώρι τους μυριοζωγραφισμένο. Καὶ γὼ ἡ φτωχὴ καὶ γὼ ἡ λιγνή, μεγάλη μέσα σ’ ὅλους, μὲ τὰ μεγάλα νύχια μου κόβω τὴ γῆ σὲ σβώλους Καὶ τοὺς πετάω κατάμουτρα στοὺς λύκους καὶ στ’ ἀγρίμια ποὺ μοὔκαναν τῆς ὄψης σου τὸ κρούσταλλο συντρίμμια. Κι ἀκολουθᾶς καὶ σὺ νεκρός, κι ὁ κόμπος τοῦ λυγμοῦ μας δένεται κόμπος τοῦ σκοινιοῦ γιὰ τὸ λαιμὸ τοῦ ὀχτροῦ μας. Κι ὡς τὄθελες (ὡς τὄλεγες τὰ βράδια μὲ τὸ λύχνο) ἀσκώνω τὸ σκεβρὸ κορμὶ καὶ τὴ γροθιά μου δείχνω. Κι ἀντὶς τ’ ἄφταιγα στήθεια μου νὰ γδέρνω, δές, βαδίζω καὶ πίσω ἀπὸ τὰ δάκρυα μου τὸν ἥλιον ἀντικρύζω. Γιέ μου, στ’ ἀδέρφια σου τραβῶ καὶ σμίγω τὴν ὀργή μου, σοῦ πῆρα τὸ ντουφέκι σου· κοιμήσου, ἐσύ, πουλί μου. You are not gone, my dear. You are right here inside my veins. Go deep inside the veins, my boy, of everyone and live. The marching crowds are passing by, on horseback and on foot. Just look at them: they’re tall and strong, as beautiful as you. And in their midst, I see you resurrected, my dear son, Your face painted a thousand times on each and every one. And I, the poor and frail one, the oldest of them all, Stoop down and, with my nails, tear the soil into clods And throw them straight into the face of all those monstrous wolves Who took your fragile beauty, son, and shattered it to bits. And you, a corpse, follow along. A knot swells in our throat And turns into the noose we tie around the killers’ necks. And, as you wished (and as you’d tell me on those lamp-lit nights), I straighten my bent body and I raise my fist up high. Instead of tearing at my breasts – they’re not to blame – I march, And through the veil of my tears I now discern the sun. I’m heading for your brothers as I add my rage to theirs. I’ve taken up your rifle, dear. You, go to sleep, my bird.

‘Astonishingly accomplished’

Mistress Quickly’s Bed