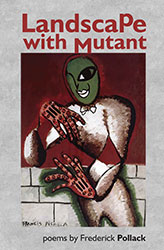

Landscape with Mutant

Frederick Pollack

Price: £8.99

‘Poetry is about something,’ according to Fred Pollack. ‘A strong poem is about something that is important, but which is not perceived by the ideologies of its time or expressible in their language.’ The poems in Landscape with Mutant are about US life before and during the Trump presidency, with its alienation, violence, and political despair. In this dystopian landscape, ‘the weak exist to be trodden and those who are trodden are weak.’ It is a book about casual racism, sharp-suited Fascism and the complicity of liberals – ‘wrinkled, blobby, obsolete, like me’ – in the assault on equality and justice. Between the narrow horizons of the mainstream (‘Have parents and write about them’) and the games of the academic avant-garde, Fred Pollack makes strong poetry about something important. ‘You can be certain you’re an enemy,’ he writes; ‘it’s your choice whether also to be a threat.’

Cover image: Front-cover: Francis Picabia,La Femme aux gants roses (Woman with Pink Gloves), also titled L'Homme aux gants, ca. 1925-1926 oil on cardboard laminate; 41 3/8 x 29 1/2 in. (105.09 x 74.93 cm) San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Fractional gift from Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photograph: Katherine Du Tiel

Author photo: Paul Kaller

Shortly after the fall of communism, I wandered through a populous city with the first of the new guidebooks. The cafe was as advertised: framed caricatures from the former era of writers and artists who had hung out there. I wondered what bureau had decided the subjects and parameters of distortion. Service was nominal, sullen, a kind of theatre, or desperately friendly – I forget. Two older guys talked, softly, clandestinely, whether out of need or habit. It wasn’t clear if their obvious dislike of me was financial (with which I could sympathize), or some nationalist-racist thing whose time was coming but not yet. One dude, perhaps a philosophy prof, was thinking, perhaps, that he should go into advertising, then remembered that he opposed advertising and returned to the Ding-an-sich and cutbacks. A woman, possibly pioneering, entered; her clothes epitomized the dowdiness of the rest. But she alone smiled, knowing that from now on no outfit would be adequate. I took out my notebook and wrote the future. Flies buzzed. Flypaper had been removed as hopelessly demode. Outside a homeless man, a member of the new International, knocked and sank to the ground beside the window, uttering those obscure remarks which, if listened to, would not have to be made.

Even a civilian may escape death many times, remembering them over the photo of a veteran with transplanted arms (not legs, unfortunately); and another, of Venezuelan schizophrenics curled on a dirty floor and chairs. But supplies of feeling (perhaps stalled for lack of appropriations in some private contractor’s warehouse) are replaced by the nullity familiar to those who serve and those who don’t who have avoided pain. The schizophrenics (the paper says) are mostly aware they’re mad and that they need drugs which are now unaffordable; those who survive will soon no longer know this, only that they’re thirsty. And the soldier, new hands limp on an oddly arranged blanket, smiles at the attractive fiancee beside him; and she smiles, inspirationally, hopefully, because what else can you do?

A million miles away, at the next table, a boy weaves, his expression bored but controlled (nice kid). The mother, mildly lined, seems there, easily coping. The sister looks farther off, perhaps at the orbit of Mars. Two old guys, heirs of the cafe wits of Paris and Vienna as this Barnes & Noble Starbucks in Bethesda is the simulacrum of a cafe, read. But those are distant stars. By the window, a youth guards a stack of car-, a girl of fashion-magazines as if they were the empire of Alexander. A black guy taps at his laptop as if each keystroke launched an empire. We are the professional classes; we keep our hands and much else to ourselves. All liberals here. When galaxies merge, individual stars almost never collide. The real threat is subtler, in the most intimate layer of space-time. At any moment, an instability could tear apart everything, down to the individual protons, leaving not even a healing, eventually formative gas. After years of work, Woodmont Avenue has crossed Bethesda Boulevard to connect with Wisconsin. At the intersection, Paul’s, Passion Fin, Pottery Barn preside, the first two with outside tables. Above them new condos with five-meter ceilings rise and gleam. They are really quite beautiful, might even subsist in some form in a just society.

The outer boughs are cartoon red, the core still pale green. Red leaves cover the slope as if they will be endlessly replenished, and there are three such trees along Whitehaven. The others, normal for a hot (the hottest) summer, dully turned dull brown a month or more ago. But the wind is properly coolish, the sky full of small, quick, doodled clouds. This street is schools, now letting out. The Catholic kids, in their uniforms, somewhat repressed; the seculars (in layers of cotton, still, not down), bouncing. The girls in their pinks and greens, especially: two twirling around their clasped hands, one skipping. (So skipping still exists!) The boys already, comparatively, lumber, and seem, whether alone or grouped, to take in little. I’m in no hurry, Mayakovsky wrote, yet shot himself an hour later. And Brecht in exile, watching a leaf fall: Tricky to calculate that leaf’s course. ough not its destination. Rush-hour begins, ever earlier; the cars along Macarthur hopefully alert for children, speed traps, and the forecast rain. You can be certain you’re an enemy. It’s your choice whether also to be a threat.

1 My calmest most sequential thoughts involve the End. Fundamentalists, plague. Jellyfish, algae. Millions of tons of methane released from tundra. Leopardi in his notebooks remarked that such reflections comfort old men. In ‘82 I knew a German girl. I was a tourist fling, she was a symbol. Preternaturally beautiful and a mean drunk, she used to look at my books and growl, ‘Why do you care about so many things? I care about nothing.’ 2 In Roman times, Sparta survived, barely, on tourism. Young aristos on the Grand Tour rode down from Corinth, complained of the bad wine and flea-ridden inns. They watched some sort of communal dance in which degenerate heirs of the hoplites mimicked the endless spear and phalanx-drill of the old days. The high point, apparently, was a bloody beating and caning of youths, who bore it impassively, and of slaves representing the ancient serfs, the helots, who were expected to cry. 3 When I teach, I feel a suspect ease that also comes when I mention teaching in poems. I have five kids this term. The department should have cancelled the class but hasn’t, and goes on paying me my smidgen. We meet in a room with no chalk, broken blinds, and an amazingly skewed chair in a corner. Outside, the new Science Centre goes on being noisily built, an institutional whimsy: they can’t afford to hire famous faculty for it, however much they raise tuition. One of my girls has read Great Expectations. A boy, an ex-jock, thinks he started it. The black kid, son of a preacher, alone gets biblical references. None of them knows any history. I’ve long since had to learn to distinguish knowledge from brains and pitch to the latter. The course is Poetry Writing. The black boy yearns for some fiery unclear apotheosis. The girl who read Dickens has always wanted to hold a book of her own; in high school she copied and bound her ‘very angsty’ work. The jock has some horror in his past. The other two, both girls, take frenzied notes. They all feel sorry for themselves and sometimes for others.

‘A didactic and cynical voice… gives the poems their bite, but also creates the tension a lot of the work relies upon for impact.’

Damfino

‘This is a great secret of his verse: he is always pushing the envelope of the image to find the after-image of the thing itself.’

Robert McDowell

‘What appeals to me most however, perhaps strangely, is an impression ofambiguity and illusion that I felt the more I read and re-read.’

Sentinel Literary Quarterly

‘The quiet solidity of these poems is a hushed plea for universal empathy, but Pollack knows the noisy voices of hate, self-regarding greed and cruelty are drowning out reason, which is why along with kindness and hope these poems enfold a sense of defeat and tragedy.’

Mistress Quickly’s Bed

‘erudite and wryly amusing, even laugh out loud funny. Pollack recognises that we are living in a kind of dystopian wilderness of cruelty, bad policies, obscurantism, xenophobia, ignorance hate and greed. Pollack is an antidote to all those negative qualities; he is a poet for this age.’

The Misfit