Lenin - OUT OF PRINT

'Never have I wanted to be understood so much as in this poem,' said Mayakovsky of his 3,000 line epic Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Written immediately after the death of Lenin's in 1924, it proudly and passionately sets the story of the Bolshevik leader's life against the history of capitalism and the trajectory of Soviet communism. By turns declamatory, lyrical, journalistic and colloquial, the poem is an extraordinary record of the utopian excitement of the early years of the Revolution - as well a warning that Lenin should not become an icon. It was Mayakovsky's most significant work; no other book of his was ever printed in such large numbers. When he read the poem to a packed Bolshoi Theatre in 1930 the event was broadcast live across the Soviet Union.

Out of print in English for over thirty years, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin remains relatively unknown in the west, where Mayakovsky is predominantly regarded as a tortured love poet. Based on Dorian Rottenberg's 1967 translation, Rosy Carrick's new bi-lingual edition of the poem firmly re-establishes Mayakovsky's reputation as one the most important political poets of the twentieth century.

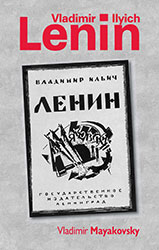

Cover image: from the edition of Владимир Ильич Ленин published by Leningrad State Publishing House in 1925.

Extract

English

The time has come. I begin the story of Lenin. Not because the grief is on the wane, but because the shock of the first moment has become a clear-cut, weighed and fathomed pain. Time, speed on, spread Lenin’s slogans in your whirl! Not for us to drown in tears, whatever happens. There’s no one more alive than Lenin in the world, our strength, our wisdom, surest of our weapon. People are boats, albeit on land. While life is being roughed all species of trash from the rocks and sand stick to the sides of our craft. But then, having broken through the storm’s mad froth, one sits in the sun for a time and cleans off the tousled seaweed growth and oozy jellyfish slime. I go to Lenin to clean off mine to sail on with the revolution. I fear these eulogies line upon line like a boy fears falsehood and delusion. They’ll rig up an aura round any head: the very idea – I abhor it, that such a halo poetry-bred should hide Lenin’s real, huge, human forehead. I’m anxious lest rituals, mausoleums and processions, the honeyed incense of homage and publicity should obscure Lenin’s essential simplicity. I shudder as I would for the apple of my eye lest Lenin be falsified by tinsel beauty. Write! – votes my heart, commissioned by the mandate of duty. * * * All Moscow’s frozen through, yet the earth quakes with emotion. Frostbite drives its victims to the fires. Who is he? Where from? Why this commotion? Why such honours when a single man expires? Dragging word by word from memory’s coffers won't suit either me or you who read. Yet what a meagre choice the dictionary offers! Where to get the very words we need? We’ve seven days to spend, twelve hours for diverse uses. Life must begin – and end. Death won’t accept excuses. But if it’s no more a matter of hours, if the calendar measure falls short, ‘Epoch’ is a usual comment of ours, ‘Era’ or something of the sort. We sleep at night, busy around by day, each grinds his water in his own pet mortar and so fritters life away. But if, single-handed, somebody can turn the tide to everyone’s profit we utter something like ‘Superman’, ‘Genius’ or ‘Prophet’. We don’t ask much of life, won’t budge an inch unless required. To please the wife is the utmost to which we aspire. But if, monolithic in body and soul, someone unlike us emerges, we discover a god-like aureole or appendages equally gorgeous. Tags and tassels laid out on shelves, neither silly nor smart – no weightier than smoke. Go scrape meaning out of such shells – empty as eggs without white or yolk. How, then, apply such yardsticks to Lenin when anyone could see with his very own eyes: that ‘era’ cleared doorways without even bending, wore jackets no bigger than average size. Should Lenin, too, be hailed by the nation as ‘Leader by Divine Designation’? Had he been kingly or godly indeed I’d never spare myself, on protest bent; I’d raise a clamour in hall and street against the crowds, speeches, processions and laments. I’d find the words for a thundering condemnation, and while I’d be trampled on, I and my cries, I’d bomb the Kremlin with demands for resignation, hurling blasphemy into the skies. But calm by the coffin Dzerzhinsky appears. Today he could easily dismiss the guard. In millions of eyes shines nothing but tears, not running down cheeks, but frozen hard. Your divinity’s decease won’t rouse a mote of feeling. No! Today real pain chills every heart. We’re burying the earthliest of beings that ever came to play an earthly part. Earthly, yes: but not the earth-bound kind who’ll never peer beyond the precincts of their sty. He took in all the planet at a time, saw things out of reach for the common eye. Though like you and I in every detail, his forehead rose a taller, steeper tower; the thought-dug wrinkles round the eyes went deeper, the lips looked firmer, more ironical than ours. Not the satrap’s firmness that’ll grind us, tightening the reins, beneath a triumph-chariot’s wheel. With friends he’d be the very soul of kindness, with enemies he’d be as hard as any steel. He, too, had illnesses and weaknesses to fight and hobbies just the same as we have, reader. For me it’s billiards, say, to whet the sight; for him it’s chess – more useful for a leader. And turning face about from chess to living foes, yesterday’s dumb pawns he led to a war of classes until a human, working-class dictatorship arose to checkmate Capital and crush its prison-castle. We and he had the same ideals to cherish. Then why is it, no kin of his, I’d welcome death, crazy with delight, I would gladly perish so that he might draw a single breath? And not I alone. Who says I'm better than the rest? Not a single soul of us, I reckon, in all the mines and mills from East to West would hesitate to do the same at the slightest beckon. Instinctively, I shrink from tram-rails to quiet corners, giddy as a drunk who sees the lees. Who would mind my puny death among these mourners lamenting the enormousness of his decease? With banners and without, they come, as if all Russia had again turned nomad for a while. The Hall of Columns trembles with their motion. What can be the reason? Wherefore? Why? Snow-tears from the flags’ red eyelids run. The telegraph’s gone hoarse with humming mournful rumours. Who is he? Where from? What has he done, this man, the most humane of all us humans? * * *