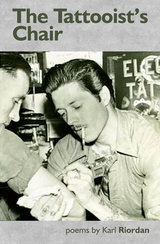

The Tattooist's Chair

Karl Riordan

Price: £7.99

Karl Riordan spent much of his late teens in a tattooist’s studio, fascinated by the declarations of love, badges of pride and intricate designs that reminded him of the Stilton legs of his grandfather, a miner tattooed by a working life spent underground. In his powerful debut collection, Riordan recalls and celebrates growing up in the South Yorkshire coalfield – holidays and haircuts, football pools and pool halls, Mackeson and Temazepam, Saturday night and Monday morning. The Tattooist’s Chair is a study in working-class history from the Barrow Colliery disaster of 1907 to the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike, St Francis in a Sheffield pet shop, Connie Francis on the dansette and Charlie Williams always having the last laugh.

Author photo: Jennifer V. Servino

‘The most disastrous colliery accident which had occurred in the immediate vicinity of Barnsley for almost a generation past, has unhappily to be recorded. The scene was at the Barrow Colliery, Worsbro’, where a cage mishap of an extraordinary nature resulted in seven men being hurled to the bottom of the shaft and instantaneously killed.’ Barnsley Chronicle, 23 November 1907 ‘…the officials speedily descended by another shaft. Here they met a horrible sight, the seven men being found lifeless, a mass of mangled humanity.’ Yorkshire Post, 16 November 1907 Thomas William Jennings Haulage Lad, aged 18 ‘Thomas Jennings stated that his lad had worked in the pit about four years. He was insured. Witness produced for the Coroner’s inspection the watch which his son was wearing at the time of the accident. It was in a celluloid case, and had apparently suffered no injury beyond the breaking of the glass. The hands had stopped at ten minutes past four.’ Barnsley Chronicle, 23 November 1907 had a key to number 2 Powell Street, where I watched my Grandad hollow out turnip brains, carve Halloween faces to shrunken heads that became lanterns we swung door to door, like Davy lamps, along terraced rows. That ignored chapping for trick or treat sweeties, like the tap, tap of the ‘Knocker-upper’ at the bedroom window, 1907. Tom props up his pillow; rests back and lights a nipped Woodbine diff, he exhales and stares at distempered walls, notes the fading rattle of sash frames then smiles at his snap-time joke on ‘Slack-Adams’. He tries hard not to be a ‘lig-in-bed’ but slinks back under the six blankets. His father’s celluloid cased watch points out two hours to go until he’ll inhale dawn air, shadowed by the towering winding wheels. The Cake Isaac Farrer, Haulage Man, aged 20 Mother ruffled up my hair today as she scuffled around the kitchen in preparation for my 21st. One more shift, before reaching my majority. Nothing is said only knowing looks, keeping me out of the way, slapping hands. My boots are unlaced warming by the fire, just like those mornings before school. She’s blind to me lifting the oven latch to peek and inhale the sweet smell of sponge taking the air from the sinking cake. William Adams Brakesman, aged 28 They nailed his father’s nickname as a child, ‘Slack Adams.’ Carrying that name like a crucifix pick over his shoulder into the dark. In secret he liked to paint, building up the layers of oil like coal. As we knit along he’s on guard against Jennings’ joke sipping on a flask of water. I overhear that name called on Barnsley market a hundred years after. Tom Rathmell Cope Hanger-On, aged 23 Mrs Sarah Cope, who was weeping bitterly, said that her husband was killed at the Swaithe Main Colliery, a mile and a half away from the Barrow pit, 16 years ago. Her son had worked at Barrow since he was 13 years of age, and was her chief support. He said “Good morning, mother,” at half-past five on Friday morning…’ Barnsley Chronicle, 23 November 1907 He’s framed, resting on the stable door this morning, thinking about their wedding scheduled for Christmas – auspicious. He listens to the sparrows, how his mother thought it lucky to awake hearing birdsong on the big day. Look at the sun when you leave for the church and your children will be beautiful. Before locking up and leaving he stands at the foot of the stairs, shouts up, ‘Good morning, mother.’ Whistles on the way to work. Walter Lewis Goodchild Hanger-on, aged 35 Polished like brown saddle leather, the penny he left under the pillow for his lad. The tooth had been loose for days and the night time groans would stir him to nudge Lizzy to tend to the child and avoid a chorus. Then yesterday, between forefinger and thumb it took some fiddling to loop string to incisor, leading twine to door handle. The fourth attempt pulled it followed by a shrill scream that would ring through the house for weeks. Byas Rooke Haulage Man, aged 22 ‘Rooke happened to be amongst the ill fated party by pure chance. He had intended coming out of the seam with his brother on the previous ascent of the cage, but stopped behind to talk to a friend, saying he would come up with the next draw.’ Barnsley Chronicle, 23 November 1907 My brother hooked his knap-sack around my neck as if awarding me a fucking medal, then pulled out his snap-tin to take a snack of half-finished bread and jam. I told him, Tha’s too much rattle thee, wanting to talk football to his mucker. I step up onto the cage, leave him dawdling underground nattering like an old woman. His face watching me ascend the shaft, we’re two coins rubbing in a waist-coat pocket. I leave pit-talk at the gate, off home, where I have to guard my language. Frank Dobson Chargeman, aged 40 They laid you out on the billiard table of the Mason’s Arms. You’ll not remember, now, that time you pocketed the cue ball for your potty. Then you took to shaping your own to the size of a pigeon’s egg, insisted upon an upturned Grimethorpe brick to rest and chip the nipsy waist height, then thwack the ovoid to the back of beyond. That park I went along to watch you in the act, the rise allowed seven times then your long knock. Of late, I walk the perimeter of the field, listening for the clack of a hickory stick.

‘An ordinary world illuminated by a seeing eye that persistently finds understated wonder. I love the poet’s ability to settle images alongside each other to show us the struggles and joys of a working class life.’

Daljit Nagra

‘Karl Riordan’s debut is a marvellous book, honest and authentic, rooted in experience. Carefully crafted and skilfully developed, these vivid, vibrant and textured poems narrate autobiographical vignettes, family memories and aspects of life in the Northern working class communities in which the poet was raised. Reminiscent of the early work of Harrison and Heaney, these deeply felt, compassionate and committed poems compel and reward re-reading.’

Steve Ely

‘writes beautifully about the South Yorkshire of his childhood and beyond.’

Ian McMillan, Yorkshire Post