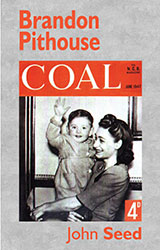

Brandon Pithouse

John Seed

Price: £7.95

There were once more than a thousand men and boys worked at Brandon Pithouse in County Durham. Today the site of the colliery is a green wilderness. John Seed has set out to recover the lost and silent world of Durham pitmen – in the company of Walter Benjamin, Sid Chaplin and Charles Reznikoff. Composed of fragments of recorded speech, parliamentary reports and newspapers, Brandon Pithouse is a book about the experience of labour – about the pain and danger of working underground, about the damage to the human body and about the human relationships created in such conditions. It is a study in the attachments and distances which shape our relationships to place and time, the negotiations required to reconnect ourselves to a world that ceased to exist in the 1990s. It is a set of notes for an unmade Eisenstein film and a footnote to chapter 10 of the first volume of Marx’s Capital. And like any history, it is a ghost story.

Author photo: Gregory Seed

6

The darkness never changes. Seasons make no difference. Spring

and summer, autumn and winter, morning, noon, and night, are

all the same.

Coal and stone, stone and coal – above, around, beneath.

There is a path which no fowl knoweth, and which the vulture’s

eye hath not seen: The lion’s whelps have not trodden it, nor the

fierce lion passed by it.

(Job 28: 3, 7-8)

_________________

they rarely saw daylight for six months of the year

apart from Sundays the whole night’s rest lasting till daylight

the one family dinner of the week

_________________

Pressing for more information, he inquired how long I had been

down the pit.

‘Seven years,’ was the answer.

In most surprised tones he said, ‘Have you not been up until now?’

I was surprised at him, and replied, ‘Yes, every day except on rare

occasions.’

‘Why, I thought you pitmen lived down there always!’

John Wilson

_________________

You do get

All sorts of temperatures

Down the mine sometimes

It’s cold as winter sometimes

Hot as hell

_________________

Youngest were the trappers of the barrow-way

where the putters pass they sit

in a hole like a chimney cut out in the coal

a string in their hand

all day in pitch black if the

candle went out or the oil ran out

noises of strata moving pieces of roof falling

rats mice scurrying round their feet

in muck and water cold and shivering

opening and closing heavy ventilation

doors for passing coal tubs

up to eighteen hours every day

_________________

Winter of 1844 we had neither, food, shoes, nor light in our first

shift.

I was sent to mind two doors up an incline and the drivers flung

coal and shouted to frighten me as they went to and fro with the

horses and tubs.

yelling all day long

half naked

black

covered by sweat and foam

The wagon-man, Tommy Dixon, visited me, and cheered me on

through the gloomy night; and when I wept for my mother, he

sang that nice little hymn,

‘In darkest shades if / Thou appear my dawning has begun’.

He also brought me some cake, and stuck a candle beside me.

_________________

To reach the pit

three miles from home

on cold dark mornings

sit crouching in a

dark damp hole behind a door

kicked and pushed

here and there among

lads and brutal men for

twelve or thirteen hours

was an experience I little dreamt of

when we asked Neddy Corvey for

work at the Leitch Colliery

_________________

10th November. – Xxxx Xxxxxxx, xx, a lad working xx Xxxxxx

Xxxxxxxx, in the night shift, had stolen some gunpowder, and

was taking it home with him in the early morning, xxx xxxxxx

xxxxx in a piece of gas piping which he had thrust down his

trouser leg to hide it xxxx xxxx, when a spark from the lamp

hanging on his belt fell into the open end of the pipe

_________________

I became a door-keeper on the

barrow-way four years ago

up at four walked

to the pit by half-past

work at five no

candles allowed except my father

gave me four burnt about

five hours I sat in

darkness the rest of the

time I liked it very

badly it was like I

was transported I used to

sleep I couldn’t keep my

eyes open the overman used

to bray us with the

yard wand he used to

leave marks I used to

be afraid the putters sometimes

thumped me for being asleep

_________________

Near a door in the rolley way I held a string which pulled open

a door and which shut again of itself.

I could move about a little but must be on the watch to see if

anything was coming.

If I happened not to open the door in proper time I was likely

to get a cut of the whip.

Swarms of mice in the pit and I could sometimes take them by

a cut of the whip.

Midges sometimes put out the candle.

The pit is choke full of black clocks creeping all about.

Nasty things they never bit me.

_________________

I often caught mice.

I took a stick and split it and fixed the mouse’s tail in it.

If I caught two or three I made them fight. They pull one

another’s noses off.

Sometimes I hung them with a horse’s hair.

The mice are numerous in the pit. They get at your bait-bags

and they get at the horse’s corn.

Cats breed sometimes in the pit and the young ones grow up

healthy.

Black clocks breed in the pit. I never meddled with them except

I could put my foot on them.

A great many midges came about when I had a candle.

_________________

I used to come up at six

went home got dinner washed and went to bed.

no mischief in turnip or pea fields

in orchard or garden

but what I was

in it or

blamed for it

when the pits were idle I wandered

Houghton-le-Spring Hetton Lambton

Newbottle Shiney Row

Philadelphia Fence Houses Colliery Row Warden Haw

Copthill

every wood dene pond and whin-cover

was known to us in our search for

blackberries mushrooms cat-haws crab-apples nuts

not a bird’s nest in wall hedge or tree for miles around

escaped our vigilance

_________________

One day the overman sent us to a part of

the mine we’d never been before there was fire-damp

put out our candles one after another as fast as

we lighted them so we ran it was not safe

to try it on any longer and we began to

scramble our way back in the dark laughing we were

a great deal but we missed our way and got

into old workings abandoned for years and got lost we

wandered about for two whole days and nights and were

nigh starved to death afore we found our way out.

_________________

many who escaped to the higher workings

must have subsisted for some time on

candles horse-flesh and horse-beans

part of a dead horse was found near and

but few candles were left

though a considerable supply had been received

just before the accident

_________________

Mushrooms

grow in the pits

at the bottom of the props

and where the muck’s fallen

100 yards or more from the shaft

_________________

‘John Seed has done it again. His historian’s mind and his poet’s ear combine to lift voices out of their documentary shafts and arrange them in artificial visual forms that slow down our reading eyes just enough so that we can hear the voices too, bearing testimony amid the statistics and documents. It’s secular magic.’

Robert Sheppard

‘John Seed is not inclined to call this work poetry but it uncertainly is – simply by the weight of the emotional truth it bears within it and through the factual interpretive discipline in the attention it pays to its fabrication. Its fluidity, its adherence to its materials, its rhythms, cadence and vernacular, produce a verity of being – the being of a way of life now gone. I implore you to read this work.’

Ralph Hawkins

‘a poetry book that deserves a place in every Durham home.’

Northern Echo

‘a fascinating poetic social document-cum-oral history.’

The Recusant

‘a cartographer of darkness... a scrapbooker of a coal town’s dark past.’

Salzburg Poetry Review