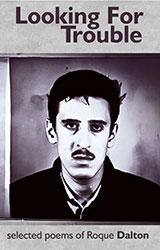

Looking for Trouble

Roque Dalton

Price: £8.99

Roque Dalton (1935-1975) is one of the best-known and best-loved poets of twentieth-century Latin America. He studied law in Chile and then at the University of El Salvador, where he helped found the Committed Generation of Poets. A member of the Salvadorean Communist Party, Dalton was imprisoned in 1959 and sentenced to death for organising students and peasants against the local landowners. On the day of his execution his life was saved when the military dictatorship was overthrown in a coup. Dalton escaped death a second time in 1965 when the prison was hit by an earthquake. He spent several years in exile in Mexico, Cuba and Czechoslovakia, where he quickly established a reputation as one of the best young Latin American poets of his generation, publishing poetry, essays, fiction and biography and winning the 1969 Casa de las Américas poetry prize. In 1975 Dalton returned to El Salvador and joined the underground Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (the Revolutionary Army of the People). Accused by the ERP of being a CIA spy, Dalton was murdered four days before his fortieth birthday.

Roque Dalton was an extraordinary poet of rebellion and humour, fierce militancy and painful tenderness, whose work should be read alongside other guerrilla poets like Otto René Castillo, Javier Heraud, Ernesto Cardenal and Daisy Zamora. Although his poetry has been widely published in Cuba, Russia, France, Germany, Italy, Czechoslovakia and the US, Looking for Trouble is the first time his work has been published in the UK.

Translated by Michal Boncza and John Green, with an introduction by Roger Atwood.

Tiene una esposa, más bien, fea. Tiene dos hijos que sacaron sus ojos y que por estos días persiguen a los gatos en el barrio. Trabaja, lee mucho, canta por las mañanas; pregunta por la salud de las señoras; es amigo del pan, el panadero; suele beber cerveza al mediodía; conoce bien el fútbol, ama el mar, desearía tener un automóvil, asiste a los conciertos, tiene un perro pequeño, ha vivido en Paris, escribió un libro – creo yo que eran versos , se siente satisfecho al ver a los pájaros, paga sus cuentas al fin del mes, ayudó a reparar el campanario… Ahora esta en la cárcel prisionero: También es comunista, como dicen…

He has a wife, rather, ugly. He has two sons who are the apple of his eye and who these days chase cats around the neighbourhood. He works, reads a lot and sings in the mornings; asks old ladies as to their health; likes bread and the baker; usually drinks beer at midday; knows all about football, loves the sea, wishes he had a car, goes to concerts, has a small dog, has lived in Paris, wrote a book – I think they were verses – he feels happy when he sees birds, pays his bills at the end of the month, helped repair the bell tower… He’s in jail now: He’s also a communist, so they say…

Es bello ser comunista, aunque cause muchos dolores de cabeza. Y es que el dolor de cabeza de los comunistas se supone histórico, es decir que no cede ante las tabletas analgésicas sino sólo ante la realización del Paraíso en la tierra. Así es la cosa. Bajo el capitalismo nos duele la cabeza y nos arrancan la cabeza. En la lucha por la Revolución la cabeza es una bomba de retardo. En la construcción socialista planificamos el dolor de cabeza lo cual no lo hace escasear, sino todo lo contrario. El comunismo será, entre otras cosas, una aspirina del tamaño del sol.

It is beautiful to be a communist, although it causes many a headache. You see the headache of communists is supposed to be historical, that is to say it does not respond to analgesic pills but only to the achievement of an earthly paradise. That’s the way it is. Under capitalism if our heads ache they just take off our heads. In the revolutionary struggle, our head is a time bomb. In constructing socialism our headaches are pre-planned which doesn’t make them rarer, in fact the contrary Communism will be, among other things, an aspirin the size of the sun

‘El marxismo-leninismo es una piedra para romperle la cabeza al imperialismo y a la burguesía.’ ‘No. El marxismo-leninismo es la goma elástica con que se arroja esa piedra.’ ‘No, no. El marxismo-leninismo es la idea que mueve el brazo que a su vez acciona la goma elástica de la honda que arroja esa piedra.’ ‘El marxismo-leninismo es la espada para cortar las manos del imperialismo.’ ‘Qué va! El marxismo-leninismo es la teoría de hacerle la manicure al imperialismo mientras se busca la oportunidad de amarrarle las manos.’ ¿Qué voy a hacer si me he pasado la vida leyendo el marxismo-leninismo y al crecer olvidé que tengo los bolsillos llenos de piedras y una honda en el bolsillo de atrás y que muy bien me podría conseguir una espada y que no soportaría estar cinco minutos en un Salón de Belleza?

‘Marxism-Leninism is a stone to break the head of imperialism and the bourgeoisie.’ ‘No. Marxism-Leninism is the catapult with which that stone is flung.’ ‘No, no. Marxism-Leninism is the idea that moves the arm that pulls the elastic of the sling that flings the stone.’ ‘Marxism-Leninism is the sword to cut off the hands of imperialism.’ ‘Nonsense? Marxism-Leninism is the theory of carrying out a manicure on imperialism while looking for an opportunity to tie its hands.’ What am I doing if I go through life reading about Marxism-Leninism and on growing up I forgot that I had pockets full of stones and a catapult in my back pocket and that I could easily get a sword and that I couldn’t stand even five minutes in a beauty parlour?

‘an excellent introduction to the work of this great Central American poet. Superbly translated.’

Latino Life

‘stands comparison with Neruda. He ought to be as well-known.’

Mistress Quickly’s Bed