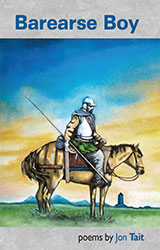

Barearse Boy

Jon Tait

Price: £7.95

Jon Tait’s family have lived in the hills of the Anglo-Scottish borders for at least six hundred years. He is a direct descendant of a notorious seventeenth-century reiver family who lived in Barearse near Yetholm in Scotland, rustling cattle, burning farms and putting their neighbours to the sword. In this modern take on Scott’s Border Minstrelsy, Tait follows the reiver people as they are forced from their rural heartlands into the industrial and post-industrial North East of England in search of work. If Kinmont Willie Armstrong were around today, he would recognise himself and his people in a book that celebrates the working class culture of the North. Written with the lawless spirit as well as the dourness and defiance of the original Border Ballads, Barearse Boy is as rooted in the purple heather moorlands of the borders as the writer himself.

Cover photo credit: Edward Martin, Scottish Border Reiver

Author photo credit: Sally Robson.

There’s a mosaic of the capture of Kinmont Willie on the underpass wall. Bearded, defiant, trussed up on horseback with a cheering crowd following behind. Funny, but they don’t have one of his escape from the square red fortress. No-one scrawls graffiti on this wall, as if his power and influence have carried on down the centuries when now he’d be sitting in a back room of a barbers, a butcher shop or bookies hair starting to go bald at the crown open-collared polo shirt the flash of gold from his thick chain against his hairy chest, holding court like Tony Soprano, hot espresso and cigarettes on his breath with his crew sat around like crocodiles. We’re all Kinmont’s bairns now.

Packed into the hall with red lodge banner loud jabbering voices of angry conversations, confusion, screeching chairs, men in black donkey jackets with orange back panels smoke drifting and clinging in yellow, grey and brown clouds we’d seen the scabs bussed into the pit with mesh on the windows like Belfast then the union man with large sideburns brylcreemed hair and crumpled white shirt tucked unevenly into a baggy suit stands at the front with arms raised as the commotion dies down and says Wuh’ve browt yuh ahl here tuh let yuh knaa whaat wuh knaa, lads. A short pause, expectation. Wuh knaa nowt. Back to the pickets, the Russian food parcels.

The seagulls lined up on the back breeze block wall shriek mockery at the goalkeeper with bobbing heads. Large empty skies grey as old chewing gum as the fog steadily lifts, revealing the red, white & blue of Union Jack flags hanging limply from the green perimeter fence. Shadowy ghosts hidden behind the nicotine-yellow net curtains of crumbling bacon & egg B&Bs with sauce clagged round the bottle top the bookies & pubs & cheap discount stores those lost names a muster call howked out of the black belly of the earth & trundled along the belt… Bates Ellington Whittle programme folded in jeans back pocket, groundsman poking a fork in the pitch. The music from the p.a. speakers distant, gone in the wind, blown out of the ground with swirling empty crisp packets. Corner flags flapping like Tibetan prayer silks.

Auld Jack played oot on the wing fought in the International Brigades in Spain & got a limp in Ebro yellow dust powdered face dull metal clang of a bullet punching into a steel helmet he copped a shard of shrapnel for the cause & married a Spanish lass that he met in the hospital who scrubbed the soot off their red terrace step & instead of olive trees saw smoke billowing out of chimney stacks a wet gleam like calm seas on the roof slates shipyard cranes peering out of the gloom & do you knaa, bonny lad, he couldn’t half cross a bahl.

‘full of energy, wit, anger, irony, joy.’

Mistress Quickly’s Bed

‘Tait pulls no verbal punches and creates a collection whose style veers between beat-generation prose poems and tenderly crafted lyrics.’

Under the Radar